- Home

- Owen Booth

What We're Teaching Our Sons Page 2

What We're Teaching Our Sons Read online

Page 2

The families of the grandfathers, everything they own packed in suitcases, waiting at the station.

And the grandfathers themselves, as boys, searching desperately through the streets for their own silent, unknowable fathers.

We tell our sons not to touch anything, even as they grab for a small model dog and accidentally sideswipe an entire bus queue with their sleeve. The youngest knocks over a crane and causes a minor disaster down at the docks. The older boys attempt to engineer horrific train crashes.

The grandfathers set about them, us, with their belts. Chase us, yelling, from the loft.

‘We forgive you!’ we scream, as the grandfathers pursue us down the street.

Women

We’re teaching our sons about women.

What they mean. Where they come from. Where they’re headed, as individuals and as a gender.

We remind our sons that their mothers are women, that their cousins are women, that their aunts are women, that their grandmothers are women. The mothers of our sons confirm their status. They’re intrigued to know where we’re going with this.

We take our sons to art galleries and museums where they can look at women as they have been depicted for hundreds of years.

In the art galleries the security guards eye us warily, watch to make sure our sons don’t go too near the valuable paintings and sculptures. There is a security guard in every room, sitting in a chair, keeping an eye on the art. The security guards are all different ages and sizes and shapes. At least half of them are women. There are arty young women and middle-aged women with glasses and older women with severe, asymmetrical haircuts.

Our sons stand in front of the works of art, under the watchful eyes of the security guards. In the works of art young women in various states of undress alternately have mostly unwanted sexual experiences or recline on and/or against things. They recline on and/or against sofas and mantelpieces and beds and picnic blankets and tombs and marble steps and piles of furs and ornamental pillars and horses and cattle. Some of the women are giant-sized. They sprawl across entire rooms in the museum. Their naked breasts and hips loom over our sons like thunder clouds.

‘Is that what all women look like with no clothes on?’ our sons ask us, nervously.

‘Some of them,’ we say, nodding, relying on our extensive experience. ‘Not all.’

Our sons gaze up at the giant women, awed. They sneak glances at the women security guards, try to make sense of it all.

‘What do women want?’ our sons ask.

We notice the women security guards looking at us with interest. We consider our words carefully.

‘Maybe the same as the rest of us?’ we say.

The women security guards are still staring at us.

‘Somewhere to live,’ we add. ‘A sense of purpose. Food. Dignity, most likely.’

‘What about adventure?’ our sons ask. ‘What about fast cars? What about romance?’

We look over at the women security guards, hoping for a sign.

We’re not getting out of this one that easily.

Money

We’re teaching our sons about money.

We’re teaching them that money is the most important thing there is. We’re teaching them that they can never have enough money, that their enemies can never have too little. We’re teaching them that money has an intrinsic worth beyond the things that it can buy, that money is a measure of their worth as men.

Alternatively, we’re teaching our sons that money is an illusion. That it doesn’t matter at all. That, most of the time, it doesn’t even exist.

‘Look at the financial industry,’ we tell them. ‘Look at derivatives. Look at credit default swaps. Look at infinite rehypothecation.’

Our sons nod at us, blankly. They’re not old enough for any of this. What were we thinking?

Together with our sons we go on the run, hiding out in a series of anonymous motels. The receptionists accept our false names without asking any questions. At three in the morning we peer out through the blinds or the heavy curtains, look for the lights of police cars out in the rain while our sons sleep.

‘Who’s out there?’ our sons ask in their sleep. ‘What do they want?’

We can’t remember the last time we slept in our own beds, cooked a meal in our own kitchens. The mothers of our sons have indulged this nonsense for far too long.

Most importantly, we’re teaching our sons how to make money. We’re putting them to work as paper boys, as child actors, as tiny bodyguards. We’re turning them into musical prodigies, poets and prize-winning authors. We’re getting them to write memoirs of their troubled upbringings. We’re using them to make false insurance claims. We’re training them to throw themselves in front of cars and fake serious injuries.

And the cash is rolling in. We’ve had to buy a job lot of counting machines.

We sit up long into the night listening to the constant whirr of the counting machines as they sing the song of our growing fortune, and we watch the rise and fall of our beautiful sleeping sons’ chests.

Geology

We’re teaching our sons about geology.

We’re teaching them about sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic rocks, about plate tectonics, about continental drift. We’re teaching them about the history of the earth, and the fossil record, and deep time.

It’s making us feel old.

Our sons want to learn about volcanoes, so we book an out-of-season holiday to Iceland. We stand on the edge of the Holuhraun lava field, staring down into the recently re-awoken inferno. Swarms of separate eruptions throw magma across the blackened, stinking landscape. Dressed in their silver heatproof suits, our sons look like an army of miniature henchmen.

We tell our sons about Eyjafjallajökull and Mount St Helens, about Krakatoa and Pompeii. We tell them how the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 led to a year without summer around the globe. We tell them about the supervolcano under Yellowstone park that may one day wipe out half the continental United States.

The spectacularly beautiful Icelandic tour guides – who are called Hanna Gunnarsdóttir and Solveig Gudrunsdóttir and Sigrun Eiðsdóttir – explain to our sons about Iceland’s geothermal energy infrastructure, how a quarter of the country’s electricity is generated using heat that comes directly from the centre of the earth.

Our sons try to get each other to run towards the lava flows, to see how close they can come before they burst into flames.

We are gently admonished by the spectacularly beautiful Icelandic tour guides for the behaviour of our sons. We are all a little bit in love with the spectacularly beautiful Icelandic tour guides. The mothers of our sons, of course, instantly become best friends with them and invite them to have a drink with us in the thermal pools.

In the thermal pools we drink incredibly expensive beers and watch the snow fall on our sons’ shoulders, settle on their hair. Our sons shiver in the brittle air, splash and jump on each other. They remind us of Japanese snow monkeys.

Hanna Gunnarsdóttir and Solveig Gudrunsdóttir and Sigrun Eiðsdóttir explain to us about the geothermal systems that heat approximately eighty-five per cent of the country’s buildings. They remind us that, geologically, Iceland is a young country: like our sons it is still being formed, as the mid-Atlantic ridge that splits the island right down the middle slowly pushes the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates away from each other.

We tell Hanna Gunnarsdóttir and Solveig Gudrunsdóttir and Sigrun Eiðsdóttir that we know how it must feel to be the western half of the country, helplessly watching the east speed towards the horizon at a rate of three centimetres a year. If only our sons were drifting away from us that slowly, we joke.

But they’ve already stopped listening.

Sport

We’re teaching our sons about sport.

We’re teaching them how to ride a bike, how to kick a ball, how to run at and go round and pick up and jump over stuff. We’re giving them suggestions on

how to choose a team to support.

Ideally we’d have outsourced a lot of this. It’s not an area we have much expertise in. We don’t tell our sons that.

‘Throw the ball!’ we shout at our sons, trying to get into the spirit of things. ‘Catch it! Pass it! Hit it with the racquet/bat/stick!’

Our sons stand in the middle of the sports field, looking at their hands like they don’t know what they’re for. Our beautiful, brilliant sons.

Our sons getting hit in the face. Our sons getting upended into the mud. Our sons getting trampled on. Our sons crashing their bikes into walls. Our sons falling off their skateboards. Our sons falling off trampolines and vaulting horses. Our sons missing catches, in slow motion. Our sons unable to climb ropes. Our sons with water up their noses, gasping for breath. Our sons slicing golf balls and swinging wildly at pitches and hooking penalties wide. Our sons tripping over their own feet. Our sons, gamely, getting back up again and again.

Our brave and magnificent sons.

We can’t take it any more. We sprint onto the field, knocking small children flying in all directions, and scoop our beautiful sons up in our arms. Wipe the mud out of their eyes, the snot from their bashed-up noses.

And then, carrying our glorious, broken sons, we run.

Emotional Literacy

We’re teaching our sons about emotional literacy.

We’re teaching them about the importance of understanding and sharing their feelings, of not being stoic and trying to keep things bottled up.

Because we are aware of the concept of toxic masculinity, we’re trying to make sure our sons grow into confident, well-balanced and emotionally open young men.

We’ve come to the park to ride on the miniature steam railway. The miniature steam railway is operated by a group of local enthusiasts who hate having to let children ride on their trains. The enthusiasts are all men.

‘How are you feeling?’ we shout to our sons, repeatedly, as we clatter around the track on the back of 1/8th scale trains. ‘What’s really going on with you? You can tell us. We’re listening.’

Our sons pretend they haven’t heard, try to ignore us. We don’t blame them. We can’t imagine talking about our feelings with other men either. The idea is horrifying. That’s why we all have hobbies.

We explain to our sons about our hobbies. About constructing and collecting and quantifying things, about putting stuff in order. Classic albums. Sightings of migratory birds. Handmade Italian bicycles. Like our fathers and their fathers and their fathers before them.

All those unknowable, infinitely quantifiable fathers.

Two of the steam enthusiasts are arguing with a customer who keeps letting his children stand up while the train is moving. Nobody wants to give ground. Eventually the customer leaves the park with his kids. He’s coming back, though, he tells us all. He’s going to sort this out.

We imagine the stand-off between the gang of ageing steam enthusiasts and the angry posse that the dissatisfied customer has, we assume, gone to recruit. The fist-fights on top of the moving trains. The driver slumping over the accelerator, the train barely speeding up, the terrifyingly slow-motion derailment, the ridiculously minor injuries. The clean-up costs and the story in the local newspaper.

‘Can we go home and play video games now?’ our sons ask.

We wonder, just for a second, how long it would take us to die if we threw ourselves in front of one of the trains. How many times we would need to be run over. How long we’d have to lie on the track. We imagine the confusion as the trains hit us again and again every few minutes, the slow realisation of what was happening, the spreading feeling of horror among the other passengers, the eventual screams.

We don’t know whether we’d have the force of will, not to mention the patience, to wait it out.

Sex

We’re teaching our sons about sex.

We’d rather not have to teach our sons about sex this soon, all things being equal. Our sons would probably rather not have to learn about sex from us right now. Possibly everyone would be a lot happier if the subject had never come up.

But we have a responsibility, we tell them, as we follow the tracks together through the fresh morning snow. If they don’t learn it from us, they’re going to learn it from their school friends and all the pornography.

The pornography is everywhere, waiting to ambush our sons. Possibly it’s already ambushed some of them. We don’t know how we’re supposed to respond to all the pornography. Obviously, we have fairly rudimentary responses to some of it. We’re not saints.

But the sheer quantity, the scale, makes us feel dizzy.

And old.

‘Well,’ say the dads among us who actually perform in pornographic films, ‘yes, but …’

‘Sorry,’ we say, ‘we didn’t mean to –’

‘No, no,’ they say, looking hurt, ‘don’t mind us trying to earn a living, trying to provide for our sons. It’s fine.’

Obviously, it isn’t fine. But, come on, nobody forced them into the business.

The divorced and separated and widowed dads among us, of course, have their own take on things. They’re back on the market, whether they want to be or not, after years out of circulation. They all have thousand-yard stares, like men who have been under shellfire.

‘It’s all different now,’ they tell us.

We stop by a silver birch tree, its branches heavy with a month’s worth of snowfall.

‘Different how?’

‘Everyone has more choice than they know what to do with. More choice and more expectations. And less hair. Nobody is expected to have any hair anywhere any more.’

We know about the hair. Everyone knows about the hair.

‘The hair thing has been going on for a while,’ we explain to our sons.

We don’t know how we feel about the hair thing. These days, we realise, we tend to look at women’s bodies with a combination of nervousness and awe. Particularly the bodies of the mothers of our sons. We’ve seen what those bodies can do, what they can take. We’ve watched them carry and give birth to and nurture children.

We try not to think of women’s bodies – and, in particular, the bodies of the mothers of our sons – as sexy warzones, sexy former battlefields, because it doesn’t seem all that respectful.

But there we are.

We wonder how useful any of this is going to be to the gay sons.

‘Oh, you have no idea,’ say the gay dads.

But the snow has started falling again, muffling our voices, turning the world back to white, and we promised the mothers of our sons that we’d all be back in time for lunch.

Plane Crashes

We’re teaching our sons about plane crashes.

We’re teaching them how plane crashes happen, how to avoid or survive being in one. We’re teaching them that plane crashes are incredibly rare, that the chances of experiencing a plane crash on a commercial airliner are approximately five million to one. We’re teaching our sons that, no matter what they’ve seen on the internet, flying is far safer than driving, than travelling by train, than riding a bicycle.

Nevertheless, by the time the plane climbs to thirty-five thousand feet, we’ve already taken the emergency codeine we’ve been saving for exactly this sort of situation.

We’ve seen those plane crash films on the internet. We know all about shoe bombs, and anti-aircraft missiles, and iced-up pitot tubes, and wind shear, and thunderstorms, and botched inspections, and pilot error. We know how easy it is to unzip the thin aluminium tube we’re sitting in; how much time we’d have to think about our fate as we fell through the frozen air, to think about the fate of our sons.

Our sons aren’t scared of flying. They’re excited about being allowed to do nothing but watch inflight movies for six or seven hours. They point down at the glorious crimson cloud tops, at the ships on the sea, don’t even notice the bumps of random turbulence that cause us to clench our jaws.

We don’t want t

o look out of the window.

We tell our sons about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who wrote The Little Prince, and who mysteriously disappeared while flying a reconnaissance mission in an unarmed P-38 during the Second World War. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, whose father died before young Antoine’s fourth birthday.

Our sons haven’t read The Little Prince, haven’t even heard of it.

‘What are they teaching you these days?’ we ask.

Our sons put their headphones back on. We know what their teachers are teaching them. They’re teaching them to be better people.

Come to think of it, we haven’t read The Little Prince either.

We stay awake all night, listening for slight changes in the tone of the engines, for the sounds of structural failure in the airframe, for sudden announcements of catastrophe. We stare down at the lights of cities, watch for panic on the faces of the cabin crew.

We keep pressing the call button to get the attention of the cabin crew.

‘There was a noise,’ we say.

The cabin crew just smile, tell us everything is going to be okay, give us more complimentary drinks.

Our sons, more used to living in the permanent present than we are, alternately sleep or watch cartoons, magnificently unaware of all the disasters that life has planned for them.

The best we can do, we realise, is to keep their hearts from breaking for as long as possible.

The Big Bang

We’re teaching our sons about the Big Bang.

We’re teaching them about the beginning of space-time, and the birth of the cosmos, and the origins of everything. We’re explaining how reality as we know it probably expanded, by accident, from an infinitely small singularity, on borrowed energy that will eventually have to be paid back. We’re trying to make it clear that we’re all potentially the result of a single overlooked instance of cosmological miscounting.

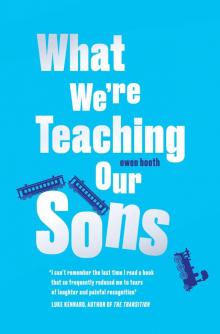

What We're Teaching Our Sons

What We're Teaching Our Sons